Introduction

This blog post follows on from a panel discussion at the LILAC 2024 conference, Information literacy : social class perspectives. Our panellists were: Jennie-Claire Crate, Darren Flynn, Rosie Hare, Ramona Naicker and Andrew Preater.

For our panel we asked LILAC attendees and others who could not attend to respond to four statements or provocations about social class and libraries with their comments and ideas. The Padlet is open in read-only mode: link to Padlet from our panel session.

In the session we drew on themes from the Padlet to inform discussion and explained we would follow up to address more of the questions and comments via a blog post which we hope will continue to spark additional conversations. We could not cover every comment without writing a post five times as long as this, so have summarised and grouped comments and ideas into themes under the original provocations we used in our panel session.

Do you agree that if you care about equity and social justice then you should include critical theories within your information literacy practice?

There were several responses in the comments, panel discussion and follow-up conversations at LILAC about our argument for the necessity of critical theories.

We chose critical theories as a term suggesting there are multiple critical traditions. However, within information literacy practice critical information literacy (CIL) is the critical approach that is most fully theoretically developed and it is CIL we centre in our work. CIL represents the application of critical pedagogy to information literacy practice and, as this approach ultimately has its theoretical roots in Critical Theory (CT), used here in uppercase to denote Frankfurt School Critical Theory, it is both radical and aligns with the social justice agenda mentioned in our provocation. We agree with the Padlet comment that CT can be employed performatively, which we take to mean employed in a shallow way for the sake of surface appearance, and we view critical librarianship not as a style to be chosen from a toolbox of different approaches in the classroom, but a thoroughgoing approach underpinning all aspects of our practice.

One unanticipated reading of our provocation is shown in the Padlet comments that we are arguing for teaching CT to students, rather than use these theories to inform our approach i.e. our practice. We agree with the Padlet comment that it is “possible to fold critical theory into our teaching as care, love without needing the ‘right’ terminology. We don’t need the discourse to value each other and respond with humanity“.

We had anticipated we might receive pushback, or unwillingness to engage with critical approaches based on a perception of these ideas being difficult, and our provocation was designed with the hope of eliciting discussion about this, and counter-arguments—as in the Padlet comment above. In the article we developed our LILAC panel from (Flynn et al., 2023) we wanted to demonstrate that working-class thought, theory and mind are not limited compared with that of librarianship’s middle-class population. We do not view our engagement with theory as limited to consumption and repetition of middle-class scholarship, but a field which we aim to enrich and transform with the development and creation of new theory.

We repeat our request to our readers from that article: “We ask those middle-class readers who find our engagement with theory challenging to keep in mind that this work was formed through our intellectual lives which are rooted in our working-class lived experiences within the academy. We also ask them to reflect on why they may wish to dismiss working-class critical theories of work and educational environments which were designed for their comfort” (p.164).

Presenting theory as too difficult, language as impenetrable, or asking for definitions of words which can be looked up online is a strategy of refusal and an excuse we do not accept. The idea that we expect students in higher education to engage and grapple with new, challenging and unfamiliar ideas is commonplace and something we agree with. We argue the same thing is true for us as lifelong learners. Refusal to engage with the meaning of critical ideas reflects privilege and falls short of the expectation we have of colleagues who hold an advanced degree in our field, or equivalent experience. What we mean by this expectation is that we know holders of a Level 7 qualification such as the library PgDip or masters have demonstrated they have “conceptual understanding that enables the student to evaluate critically current research and advanced scholarship in the discipline,” and can “continue to advance their knowledge and understanding, and to develop new skills to a high level” (QAA, 2024 p.24).

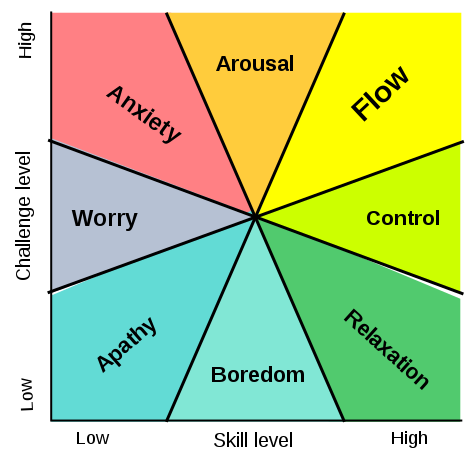

We believe we can trust in our colleagues’ ability to look up the meaning of any terms that are unfamiliar, and think about how theory might be applied to their practice. We know it requires a level of engagement and vulnerability to understand that you may be an absolute beginner, or may never reach deep expertise, but the work is still necessary.

This is hard work, and is supposed to be hard because any work that focuses on how different people have been oppressed over the years will involve unpacking the feelings, knowledge and assumptions you hold within yourself, and looking in the mirror at how you’ve benefited from certain privileges—especially as a white, middle-class person. This is the hardest work, because you have to be fully honest with yourself and to be progressive implies this is work that is never finished. There is a real need to sit with our discomfort.

We can, in our practice cite and utilise authors who do this sort of theoretical work without recourse to over-complex language such as Audre Lorde, bell hooks, Patricia Hill Collins and Gloria E. Anzaldúa. This also connects with the strengths in knowledge that working-class students bring to academia, as bell hooks writes, “Importantly, one need not be either intellectual or academic to engage in critical thinking. Everyone engages in thinking in everyday life” (p.187). Engaging with CIL benefits our teaching practice as its theoretical body of knowledge helps open students’ eyes to structural inequalities, preparing them to handle diverse perspectives and challenges in a pluralistic society. Adopting a critical approach to information literacy strengthens teaching, but also facilitates meaningful dialogue among students from varied social class and socioeconomic backgrounds, fostering empathy and a collective commitment to tackling social justice issues.

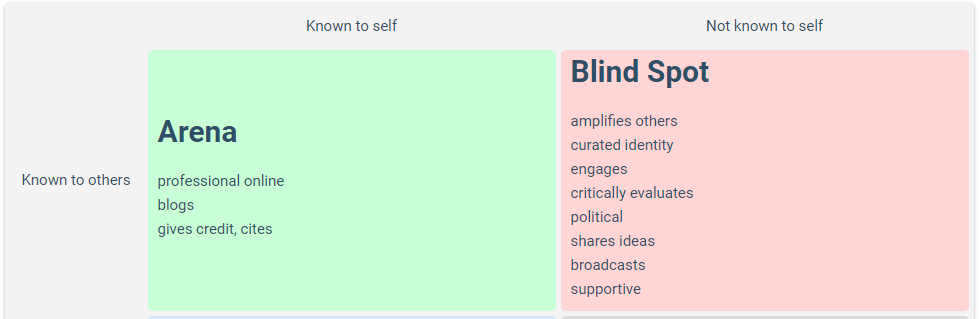

We observe librarians are unaware of how middle-class librarianship is. How do you think this permeates our teaching environments as a form of shared knowledge?

This comment in the Padlet demonstrates an excellent example of the kind of reflective praxis that this work involves, and shows how critical self-reflection isn’t an academic exercise but a necessary part of our professional growth: “I’m a white extremely middle class librarian serving a population that is mostly not white and mostly not middle class and until I started examining that and working on myself, I wasn’t serving that population properly. I’m still working on it but I’m much better and it shows in the better way I can advocate for my students.” This work does not involve throwing our hands up and despairing at how we aren’t getting it perfect straight away. We all have certain privileges we need to examine before we are better able to understand and work with the various forms of capital and community cultural wealth (Yosso, 2005) that students bring to education settings. This work enhances our professional practice, but also ensures we are genuinely meeting the diverse needs of our student population, rather than perpetuating outdated and exclusionary standards.

In the comments for this provocation there is a theme about assumptions colleagues make about common—meaning shared—knowledge staff and students have, which is in fact knowledge common to the middle class. This knowledge informs our assumptions about what information literacy actually is, and how and what we teach. Librarianship inherits the middle-class norms and values of the academy and our colleagues, and one challenge to ourselves is to ask what our responsibility, or ability is to influence and change this. This is work that lies outside ourselves, that implies change in a wider social system based on hegemonic norms, values and assumptions. Attempting to influence that system can be a deeply frustrating experience. Hegemony means the dominance of a social group based on the cultural outlook or worldview of a ruling group, such that it becomes viewed as a natural or inevitable cultural norm. These frustrations act individually, as the needs and perspectives of our working class colleagues are overlooked, and structurally as this reinforces a cycle of marginalisation within our educational settings and curtails innovation in librarianship. We argue that we can at least be prefigurative in those areas that we can influence: we can always, at least, role-model the approach and behaviours we wish to see as the future norm.

There is a Padlet comment, and were contributions in the LILAC panel from librarians from outside the UK about our class system. The panel was speaking from a perspective of experience limited to the UK, and we welcome reflections from those—particularly of working-class origin—who had not grown up here. This is an ongoing conversation and, as stated above, this work is never finished.

We ask if you feel uncomfortable reflecting on classism and class privilege in your work and information literacy practice, to ask yourself why that might be?

A key theme we draw from responses to this provocation is the discomfort felt by our colleagues of working-class origin who have attained middle-class income or other markers of status due to social mobility, and work in middle-class environments such as higher education where a sense of difference or ‘not fitting in’ is still felt by those who have crossed this divide.

We do want to draw a distinction between social class and socioeconomic status (SES), which are often conflated. Both of these concepts describe social stratification but SES considers socioeconomic factors such as employment, income and education level whereas social class relates to sociocultural factors and one’s relationship to social power (Manstead, 2018). SES can change rapidly throughout one’s life, whereas social class is inherited and relatively stable throughout one’s life course. This means that those of working-class origin who have experienced this migration will have improved their SES, but retain their position in terms of social class.

These feelings of dislocation are familiar from research on sociology of education and social mobility, described by Teresa Crew as “a set of dislocating symptoms produced by the reconciliation process between a working-class identity and the hierarchically organized field of academia” (2020, p.32). We also saw in the Padlet comments and panel discussion mention of imposter phenomenon, meaning feelings of intellectual phoniness (Clance and Imes, 1978) based on class position, including being driven to imitate middle-class social mores to better fit in.

Conversely, this understanding of difference can inform and enrich our interactions with our students and provide moments of critical reflection. In the Padlet there are some breakthrough critical reflections on one’s own class privilege and intersectional identity, which represent positive moments demonstrating growth and understanding. There is a need to sit with the discomfort of these realisations that, as in the comment which references Robin DiAngelo (2018), “Even though my family was impoverished, I only realised that I am privileged on account of my skin colour after reading ‘White Fragility’”, and “It hurts to start realising that you are in fact the oppressor in some circumstances, when you are used to seeing yourself as the oppressed”.

This work is intersectional: we argue for an intersectional politics of class rooted in critical self-inspection. Unpacking your own class privilege needs to include and be informed by inspecting your privileges around race, disability, sexuality, gender identity, neurodivergence and other aspects or facets of identity. We reject hard-right and Conservative reactionary discourses about the white working class: librarianship remains a very white profession with less than 5% of the workforce identifying as a global majority ethnicity (CILIP, 2023) and this needs to be improved. This monoculture—the dominance of white perspectives in librarianship—is reflected in these workforce demographics and also influences the research and scholarship within our field, often sidelining the diverse experiences and needs of global majority communities.

If you identify as middle class, what steps could you take in terms of allyship or as an accomplice to challenge social class elitism in your information literacy practices and workplace?

The problem of classism in higher education is an embedded, complex structural issue that must be met structurally and as such, we do not aim to present quick tips which we know will not affect meaningful change.

One thing we consider a key practical step is working on one’s self to gain the type of breakthrough critical reflections we describe above, which are rooted in understanding one’s own positionality and privilege. Positionality means one’s social location in terms of facets of identity, and one’s social and political context. Again, this work can be some of the hardest to do, because it is thankless: nobody will pat you on the back or give you a gold star for your good allyship. Many who do attempt to complete social justice work in their workplaces experience pushback, as their colleagues become uncomfortable when a mirror is held up to the practices that have served them well for years. For those who are middle-class or who have migrated into the middle class via social mobility, these actions may be viewed as a betrayal by their peers who do not want to cede their unearned benefits of class privilege. Overcoming people-pleasing as a profession that is made up of 75% women (CILIP, 2023), where women are predominantly socialised to be accommodating and amenable, is difficult work involving significant reflective practice and vulnerability.

We can however utilise the privilege we do have to improve things, where we can. This can include everyday actions of solidarity, as one comment in the Padlet reads, “Call[ing] out the bullshit from my fellow middle-class colleagues”. This still comes with some measure of risk, even for small actions, as colleagues’ reactance and hurt feelings can be out of proportion to the action being taken. As one action of recognition and solidarity we can bring to our professional practice and share, if we have these, working-class lived experiences with working-class students and colleagues. We also can work on sympathetic or empathetic understanding of others’ experiences, and work against our own immediate assumptions. Related to this, we can work on our assumptions about our students’ knowledge of unspoken rules—the so-called hidden curriculum—and our assumptions about previous experiences of libraries from their previous educational experiences. It is crucial to acknowledge that individuals from minoritised groups often face additional hurdles and have often had to work harder to overcome these systemic barriers to achieve their current position. We need to continually challenge our assumptions about what students know, and how they interact with us and our collections. We can also call out snobbery around colleagues’ assumptions based on students’ outward markers of social class such as fashion, accents and dialect. Importantly, as Teresa Crew (2020) explains in her research on working-class academics; making the hidden visible works as both a strategy for challenging assumptions and classist microaggressions (p.88) and in terms of connection with students by sharing understanding rooted in shared lived experiences (pp.118-120).

We are stewards of our libraries and learning spaces, and can work to develop them into places of welcome rather than of exclusion. One person who commented on the Padlet and works in further education said, “I have noticed that a lot of students seem hesitant to come in and ask if it’s “allowed” to sit at a table or use a PC,” and that deliberate relaxing of rules that has led to more positive student behaviour as, “it no longer feels like a place where there is an unwritten assumption that everyone knows how libraries work and that there is an expected way to spend your time there”. This comment, and discussion from an audience member at LILAC about their work to mitigate fear felt by students who had not used libraries before, reflect approaches to reduce feelings of library anxiety, which are feelings of inadequacy and lack of skill when confronted with the size and complexity of academic libraries (Mellon, 1986). In our article, we also identify as one cause the architectural scale and grandeur of academic library design that prioritise middle-class tastes and preferences (Flynn et al., pp.171-172).

Finally, there is a comment on the Padlet that makes a structural point about reducing barriers to entry and progression to senior roles within the profession, as “Despite recently introducing apprenticeship positions in the library, we still ask for postgraduate qualifications for more senior roles but don’t offer financial support to allow junior colleagues to pursue these.” Employers in our sectors already use the Level 3 Library, information and archive services assistant standard as an alternative to hiring graduates into library assistant roles (which is classified as a non-graduate role by the UK government). We acknowledge this standard can be misused by employers, for example by paying apprentices less for the same work as other staff.

One near-future possibility for our workplaces is using the Level 7 Library, information and knowledge professional standard as an alternative to current qualifications like the PgDip or masters, anticipated later in 2024. Introducing these to our workplaces does require positional power and senior leadership support, alongside this it is crucial that leaders and hiring managers give genuine equivalence to this route as there is a risk the cultural capital embodied in postgraduate qualifications leads to disadvantage for those coming via the apprenticeship route. Our sector has generally not done well at keeping up with qualifications frameworks, recognising non-academic routes or expressing parity of esteem (Fair Library Jobs, 2023). However, advocating for these apprenticeships, responding constructively to sector consultations about apprenticeships in our sector and raising awareness of these as an option in our workplaces—including helping dispel myths—is open to all of us. By creating pathways for individuals from diverse backgrounds to enter and advance in our profession, we not only enrich our libraries but also demonstrate practically our commitment to inclusivity and equity.

Conclusion

As a panel we want to extend our grateful thanks to the contributors to our Padlet both ahead of time and in the session, and those who contributed on the day at LILAC. Your thoughts and ideas made the discussion as rich as it was—thank you.

As we said on the day to our colleagues and friends of working class origin in the audience, we have done this for you. We wanted you to feel seen and recognised, because we know this is not the norm in librarianship. We hope we met this goal in our session and have represented the same spirit in this follow-up piece. Moving forward, we encourage each one of us, regardless of our class backgrounds, to continue these conversations in our own libraries and communities.

References

CILIP (2023) Workforce mapping 2023. Available at: https://www.cilip.org.uk/page/workforcemapping (Accessed: 15 April 2024).

Clance, P.R. and Imes, S.A. (1978) ‘The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: dynamics and therapeutic intervention’, Psychotherapy, 15(3), pp.241-247 [Online]. doi:10.1037/h0086006.

Crew, T. (2020) Higher education and working-class academics: precarity and diversity in academia. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

DiAngelo, R. (2018) White fragility: why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism. Boston, MA: Beacon.

Fair Library Jobs (2023). On qualifications – part 1. Available at: https://fairlibraryjobs.substack.com/p/on-qualifications-part-1 (Accessed: 18 April 2024).

Flynn, D., Crew, T., Hare, R., Maroo, K., and Preater, A. (2023) ‘They burn so bright whilst you can only wonder why’: Stories at the intersection of social class, capital and critical information literacy – a collaborative autoethnography,’ Journal of Information Literacy, 17(1), pp.162-185 [Online]. doi:10.11645/17.1.3361.

hooks, b. (2010) Teaching critical thinking: practical wisdom. New York, NY: Routledge.

Manstead, A.S.R. (2018) ‘The psychology of social class: how socioeconomic status impacts thought, feelings, and behaviour’, British Journal of Social Psychology, 57(2), pp.267-291 [Online]. doi:10.1111/bjso.12251.

Mellon, C. (1986) ‘Library anxiety: a grounded theory and its development’, College & Research Libraries, 47(2), pp.160-165 [Online]. doi:10.5860/crl_47_02_160.

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) (2024) The frameworks for higher education qualifications of UK degree-awarding bodies. Available at: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/quality-code/the-frameworks-for-higher-education-qualifications-of-uk-degree-awarding-bodies-2024.pdf (Accessed: 15 April 2024).

Yosso, T. J. (2005) ‘Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth’, Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), pp.69-91 [Online]. doi:10.1080/1361332052000341006.