This blog post also appears on the uklibchat site for the chat of 6 August 2013, ‘The changing world of libraries and information‘. This post contains an additional reference to a blog post by the Library Loon on ‘steady-state librarianship‘ which was omitted from the version published by uklibchat – my error.

I have to change to stay the same

– Willem de Kooning

In this guest blog post for uklibchat I’ll talk about how I deal with change in my role at Senate House Libraries, University of London.

For my library masters I studied various models for describing change and how to manage change. I won’t dwell on these in detail but to give one example to think about, Lewin’s (1947) model describes change as a three step process:

- Unfreezing: preparing the organization for change, building a case, dismantling the existing “mindset”.

- Change: an uncomfortable period of uncertainty with the organization beginning to make and embrace changes.

- Freezing: finalizing the organization in a new, stable state and returning to former levels of comfort.

I use this model as a way of understanding a traditional view, sometimes presented as a “common sense” view, of change processes though I find the underlying assumptions in the model itself quite manipulative – for example the idea that to create change, the transient pain of change must be understood to be less for the organization than the pain of keeping things the same. Other models have more steps and so greater complexity. Kotter’s (1996) eight step change model is one example; at that level of complexity it reads more like “Kotter’s tips for implementing change” rather than a theoretical model.

The main things I take from these models and work experience are that:

- The major challenges in implementing change come down to people rather than technology or machines.

- The period of implementing change will be disruptive and uncomfortable, as a manager you cannot ignore but must engage with this.

- Communication at all stages is key to a successful change process – including celebrating success afterwards.

At Senate House Libraries we’ve experienced a considerable period of disruptive change since the mid-2000s. One conclusion I’ve made from this is we are definitely no longer in the business of steady-state librarianship (Library Loon, 2012). Our “business as usual” now includes an implicit assumption that we need to constantly review and adjust our processes and services to meet changing needs and demands, hence my inclusion of Willem de Kooning’s wonderfully mysterious quote above.

This does not mean slavishly following every new trend in technology or being led by the nose by technology, particularly technology as repackaged and sold by library software and hardware suppliers, but actively maintaining current awareness and honestly evaluating the status quo as thoroughly as we do new ideas.

I say this because in some libraries I notice a willingness to subject the new thing in a change process to exacting and rigorous examination but not examine the status quo in the same way. There is an assumption here about the ‘rightness’ of our current approaches, whatever they happen to be. What I find troubling about this is the idea our way of working will remain ‘right’ for any length of time in a changing landscape. It is absolutely right not to try to fix something that isn’t broken or enact change for the sake of change, but this is something only knowable following evaluation.

For me the operational aspect of library service must inform strategic thinking and planning, as it’s those staff that are in constant contact with library members and understand the fine detail of the service. For this reason I involve my whole team in developing operational plans and contributing to strategy by identifying priorities for future work. My view is change shouldn’t just be something that ‘just happens’ to staff but something for all to take an active role in.

Personally I am influenced by approaches from IT as I have a systems background, and more broadly am influenced by application of researched-based and evidence-based practise in librarianship. To be clear I include qualitative research in this as an essential parter to quantitative research, adding much-needed richness and depth to our understanding of user experience and behaviour.

One change process at my workplace where I’ve used this approach is implementing a new discovery layer, or library catalogue, as part of our implementation of a new library management system, Kuali Open Library Environment (OLE). OLE does not have a traditional catalogue so a catalogue or discovery layer such as VuFind or Blacklight is needed.

To do this, we have built and developed the case for changing by:

- Presenting about the project formally at all-staff meetings and individual team meetings.

- Informal conversation with staff to answer questions and build awareness ‘things are happening’ around discovery.

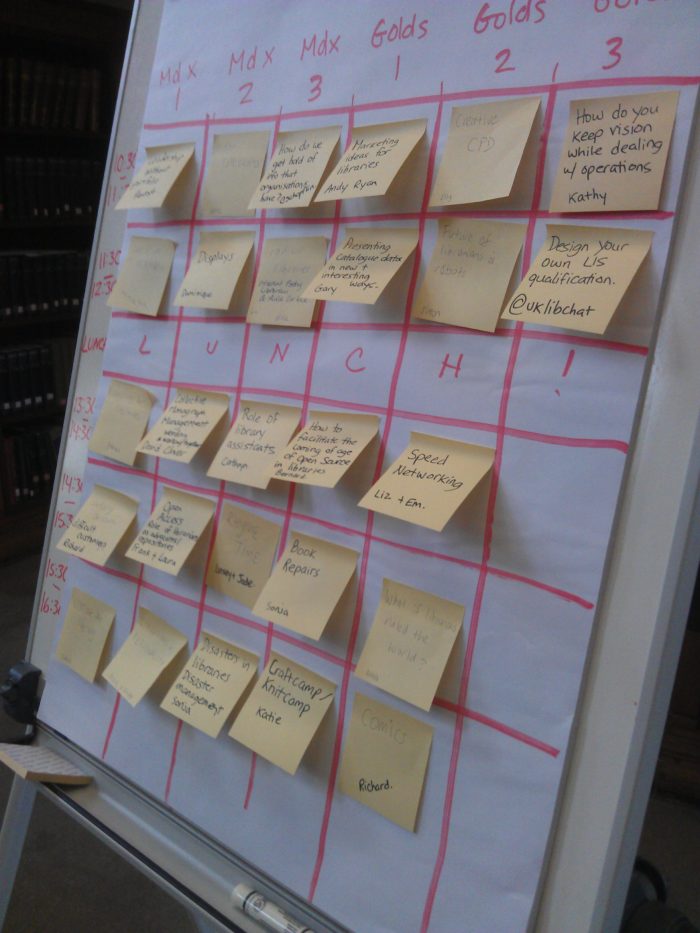

- Involving staff in thinking creatively about discovery in a workshop environment (I blogged about this aspect a few months ago).

- Giving discovery the respect it deserves by treating it as a Web project that puts user experience at the core – and being seen to do so. This includes hosting a student from UCL Department of Information Studies doing ethnographic research on catalogue user behaviour.

- Answer technical questions quickly and with confidence, including in-depth questions about SolrMARC (really) and metadata issues.

The important point for me as the head of our systems team is so much of this is not about technology, it’s about surfacing opinion and including staff in conversation. For example we’ve set up a beta test VuFind 2.0 instance to provide food for thought, but it’s not core

By necessity this blog post is brief, but I hope this specific example and the more general things I’ve said above help seed discussion for uklibchat.

References

Lewin, K. (1947) ‘Frontiers in group dynamics: concept, method and reality in social science; social equilibria and social change’, Human Relations, 1 (1), pp. 5-41, PsycINFO [Online] doi:10.1177/001872674700100103 (Accessed: 27 July 2013)

Kotter, J.P. (1996) Leading change. Watertown, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Library Loon (2012) ‘Steady-state vs. expanding-universe librarianship’, Gavia Libraria, 22 July. Available at: http://gavialib.com/2012/07/steady-state-vs-expanding-universe-librarianship/ (Accessed: 7 August 2013).