This blog post is modified from a talk I gave for #CityLIS at City, University of London on 19 March 2018.

This seminar explored the idea and the various meanings of critical librarianship as a concept, practice, and area of intellectual enquiry. Critical librarianship is multifaceted and includes a body of scholarly work that employs critical frames for theorising libraries and information; activist and social justice-oriented stances within library work; online communities and discussion spaces such as #critlib chat; and more. Its focus on scholarly thought and theory has been criticised as removed from the practical concerns that confront library workers and the communities they serve, whereas its more practical suggestions and ethical approaches are sometimes read as just good librarianship. Here I will give my view on what I think critical librarianship to be, and what I think it has to offer in practice.

A comment on terminology, below I am using ‘librarianship’ interchangeably with ‘library and information science’ (LIS), ‘critique’ interchangeably with ‘criticism’, and will prefer ‘library workers’ to ‘librarians’.

Context

At this point I discussed how our economic system tends to introduce market logics and measurement techniques into many or perhaps most areas of human activity. Rather than recount this, I will recommend the recent exploration and critique of this trend applied to education presented in Professor Roger Brown’s lecture Neoliberalism, Marketisation, and Higher Education – University of West London public professorial lecture.

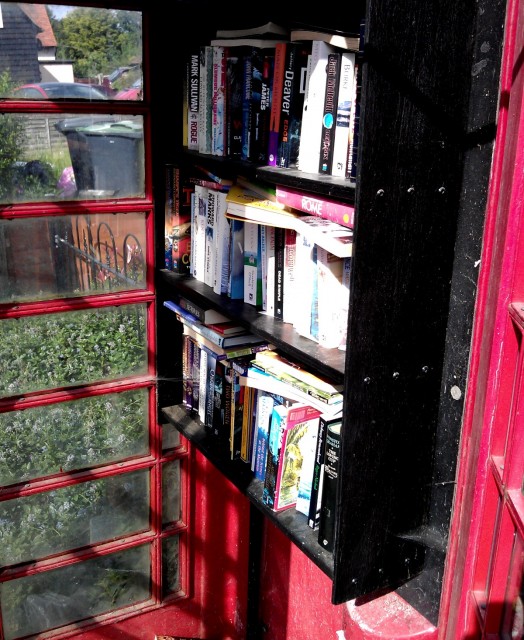

In our context, libraries and library workers have struggled to maintain and demonstrate relevance and have repeatedly sought to emphasise the value of libraries primarily based on a market logic. This includes for example comparative usage statistics for library services, and a recent focus on the value added by our basic disciplinary expertise of information literacy.

You may know of Cilip’s campaign about information literacy related to fake news and political information. Facts Matter is rooted in an approach that values critical thinking and reading of political information so broadly I support it; the issues I raise today are more rooted in the question of what facts are. In my view, fake news, the concept of post-truth and the absurd notion of alternative facts don’t sit in the same dialogical space as facts or meaning-making do intrinsically. They are more about a constant steady drip of propaganda, influencing at scale, and the expression of a prefigurative practice for particular political causes—especially far-right or fascist politics.

Critique and the critical

I want to spend some time discussing what we actually mean by the critical, because this is a contested term with multiple meanings. I’ll present a particular view of this using a frame based on critique as method—a method to direct and inform action that carries social and ethical implications beyond the technical execution of library work. I also want to address how we can pay critical attention in practice, here we will focus on critical reflection. First let’s stop for a minute to inspect and problematise the word ‘critical’ and the basis of librarianship as discipline.

Historically, and regrettably in my view, librarianship has attempted to define itself and prove itself as a social science—based on positivist and post-positivist ideas and quantitative methods.

Critical…

Thinking

Reading

Literacy

Pedagogy

Reflection

Theory

Librarianship?

Readers will have heard of at least some of these concepts and certainly will be familiar with concepts like critical reading and thinking in more depth. I explained the to audience that as students, I am certain you read critically within the LIS literature; I am sure you think critically about theory and ideas; I am confident you reflect on practice.

A common position in our discourse is a focus on critical thinking and reading as the critical. Stereotyping, this means forming judgements as to what is true and correct, about what is factual in positivist terms following an objective and neutral process of evaluation. This can present broader ideas of criticism as similarly naive, as a negative dialectical approach or as something that is not much more than a practical tool for problem-solving. I will describe an approach based on a different concept: that critique is about the questioning of social norms and cultures that shape and constrain our day-to-day approaches and work.

“Critical thought and its theory…”

Horkheimer, 1972 p.210

This is rooted in critical theory (sometimes presented with a capital C and a capital T). As a school of thought critical theory maintains that ideology is a principal obstacle to human liberation and originally sought to radically critique both the fabric of society and traditional theoretical approaches that came before. Critical theory in the mode of Adorno, Horkheimer and other thinkers of the Frankfurt School sought to identify and lay bare these ideologies. Note that this school of thought is reasonably left-wing.

“Critical theory is like any language; you can learn it, and when you learn it, you begin to move around in it.”

Ahmed, 2017 p.9

I would like us to take a wider view than Frankfurt School critical theory applied to librarianship. Sara Ahmed’s use of metaphor here resonates with me in how she describes the slow process of discovery and understanding that allows us to explore new disciplinary areas and “move around in” them. My point in citing this is that critical theories and approaches are something we can all gain understanding and knowledge of, whatever our educational groundings or backgrounds.

“Without a vision for tomorrow, hope is impossible.”

Freire, 1997 p.13

Before we move on, let’s spend a little time with Paulo Freire and critical hope. Freire is an inescapable influence within critical librarianship, in large part due to the influence of critical pedagogy on contemporary critical information literacy teaching practice. Freire championed a radical, anti-colonial ‘problem-posing’ method of education intended to consciously shape learners and lead them to develop critical consciousness with which to overcome oppression. For Freire, hope is a foundational requirement for education because it is hope that drives people to pursue completeness as human beings: to explore, interrogate, to question, and to learn. As library workers, we understand leaning as a lifelong process and this pursuit is not something that ends at school-leaving or graduation.

Where is the critical librarianship?

Examples of critical practice applied in the form of practical actions abound, and library workers enact critical practice even if it is not explicitly framed in the language of critical librarianship. I want to reiterate this practice element here, and give some examples of the importance of action.

https://twitter.com/edrabinski/status/717053814373793792 [deleted tweet]

Emily Drabinski’s point here is about the everyday ways in which we remake structures and systems by thinking about them and questioning them day by day. (The comment “Me too!” is agreement with the quoted tweet.) How about some more comments from practitioners?

“I use theory literally every day to inform the shape of the searches I perform, the summaries I produce, and the support I give to [social services] practitioners.”

Smith, 2018

Lauren Smith develops information services for social services practitioners across Scotland. She explains here this is a necessarily theoretically-informed practice at all levels, with theory utilised daily in practice in all aspects of work. In this way theory is applied in an integrative approach, there is no pause where the practitioner steps outside into a realm of theory to cogitate before returning back to the everyday world of practice.

“It is assumed that taking a critical perspective in a corporate information role is impossible because ones workplace goals are aligned with those of the organisation. However […] organisations hire information professionals to uphold standards of authoritative research, ethical resource use and high information literacy. Of course it can be difficult to challenge organisational hierarchies, and you may not get the support you need to do so, but this is actually true of all information work.”

Schopflin, 2018

Katharine Schopflin explains that the role of information professionals within organisations always implies that we maintain an ethical stance related to the standards of our profession—that is formally what we are hired to do, regardless of the sector or industry we are working in. Of course, we see how tensions can and do emerge in some work environments.

Q1 #uklibchat pub lib staff are desperately trying to keep the doors open & management don't tend to promote critical thinking.

— Alan Wylie (@wylie_alan) June 6, 2017

Practitioners coming from critical positions are often offering us a reading against the grain of dominant cultures in workplaces and professional contexts. This can be the case in public sector or publicly-funded environments as much as corporate information roles, which may be due to funding and resourcing pressure as much as an ideological position (funding choices are, of course, themselves ideological positions). As Alan Wylie points out here, many public library workers have enough to do just keeping libraries running and operating effectively in environments where critical approaches are not particularly valued by their leadership.

As an aside, I personally believe one of the most valuable things managers can give teams is the time and space as well as the supportive context to do such thinking alongside the day-to-day.

Critical librarianship, a developed theoretical frame

#Critlib is now poptimism or sabermetrics, an outsider perspective that's become the mainstream of high-level professional discourse.

— Al (@__al_b) May 25, 2017

This quote refers to an analysis of one information literacy journal, Communications in Information Literacy, that showed the most common theoretical frame used was critical information literacy (Hollister, 2017). It’s surprising and exciting to see reports like this. However, this can overstate the extent to which library workers more widely adopt critical practices, as it is specific to one context: application of critical pedagogy to information literacy practice in North American academic libraries.

“Our work […] must be critically informed, dialogically inventive, and messily entrenched within the systems we are working to change.”

Almeida, 2018 p.254

I would like to make a case for more widely-embedded critical approaches in practice. This is Nora Almeida’s view from the recently-published The Politics of Theory and the Practice of Critical Librarianship (Nicholson and Seale, 2018). I agree with this as it feels like a solid justification for the critical rooted in the effectiveness of what we do in practice; and in how practice is “messily entrenched” (a wonderfully #critlib term) in our work and lives rather than something to do as an optional add-on to real work. This talk is not about practical tips for your CPD, especially given that I want to stay true to the theoretical basis of critical reflection discussed below, but I do want to explore the value of critique compared with the hundreds of other things you could spend time on.

“By critique I am referring to that praxis that refuses and thus disrupts a calcified and definitive way of understanding difference, subjects, and subjectivity.”

Dhamoon, 2011 p.239

In this article Rita Dhamoon introduces a idea of critique as a practice or praxis (with an x) of refusal: a disruptive, and, we can imagine, a necessarily confrontational approach that aims at creating change for a particular direction and purpose. In the talk I argued that critique can aid in development, in inculcating resistance, and in improving equity and equality. Here I am imagining critical thought supporting and aiding progress toward and the achievement of our goals, rather than as a tool we draw from our toolbox for day-to-day problem-solving. I argue critique offers a unique set of dialogical methods for approaching our work broadly—within and outside workplaces, and in practice more broadly.

Praxis‽

I could go the rest of my life and never make a slide as good as this one. #claps2016 #critlib #sneakpeak #spoilers pic.twitter.com/Y7DmWlvAoj

— Kevin Seeber (@kevinseeber) November 20, 2015

So, praxis ‘with an x’. In the talk I defined this as an integrative approach to critically thinking about and actively engaging with the world based on theoretically-informed reflection and action. In this I drew on Freire (1997) and Arendt (1998); for me a framing that includes both elements of critical thinking and reflection is key. I feel ‘reflection’ as a word does us disservice in the image it creates in our minds of contemplative mulling-over that does not necessarily go anywhere, hence I emphasise here action based on deepened insight.

At this point I asked the audience to consider, does anyone think they already take this approach in practice? My suspicion is that many of us do.

Critically reflective practice

I would like to relate this specifically to reflective practice, as that is one way we can embody a critical approach in what we do.

“The development of insight and practice through critical attention to practical values, theories, principles, assumptions and the relationship between theory and practice which inform everyday actions.”

Bolton, 2014 p. xxiii

This is a definition of reflection from Gillie Bolton. The critically reflective question to drive toward deeper meaning and understanding is to always ask why. The key point to pick out is about “critical attention to practical values”. What Bolton does here is a useful rhetorical reframing that may benefit you in practice. I find that often when I discuss theory in general terms I find that it is more relatable instead to talk about values. It is more alive, more rooted in experience, and is something we can all relate to no matter what we read.

“Critical reflection involves asking what questions, issues or ways of thinking have been privileged by whom and for what reasons? This type of reflection aims to address concerns about the influence of powerful groups by acknowledging and surfacing different interests and agendas.”

Smith, 2011 pp.217-218

Linking reflection to action is the enactment of critical practice, with a central element in critical attention to and examination of our underlying values, assumptions, and beliefs and linking these with our political, ethical, and social contexts. This may seem overly-introspective at first; but at this point I want to bring in Elizabeth Smith’s perspective relating power and privilege to the social in reflective practice. This is very much an outward-looking approach that situates our work within multiple, necessarily social, contexts of which we need awareness to form balanced judgements.

“When we only name the problem, when we state complaint without a constructive focus or resolution, we take hope away. In this way critique can become merely an expression of profound cynicism, which then works to sustain dominator culture.”

hooks, 2003 p.xiv

As good as this may sound, there are dangers here linked to the negative aspects of critical reflective practice. bell hooks cautions here about critique fermenting a world-weary cynicism that leaches hope, and rather than transformative change leads to an acceptance of “dominator culture,” which is to say the dominant or hegemonic practices that reinscribe inequality and oppression.

A fundamental here is the link with how we reflect on practice and shape it in action. In my view, the strategic critical moves to make are those that work at or work towards transforming rather than reforming. At this point I cited Archie Dick (1995) who describes a progressive, transformative, and explicitly Foucauldian current in librarianship that is noticeably well-aligned with contemporary critical librarianship. Here I paraphrase from Dick (p.229), this camp argues for:

- Critique of our own approaches and practices in stock selection, cataloguing and classification to highlight assumptions and biases. Brought up to date, we could add algorithmic bias in search and discovery.

- Raising the critical consciousness of library workers in understanding non-neutrality of libraries.

- Library educators to appreciate and critique power relations within LIS theory.

- Pushing back on “creeping marketisation” of libraries, especially that based on the notion of information as a commodity.

Power and questioning critically

I’d like to deal with some aspects of power, for this I will briefly drop into Foucault’s work. I realise that like Freire, this is a very #critlib citation. However, I have found Foucauldian methods of analysing power transformative, and wanted to provide a worked example as well as a caution.

“Power relations are rooted in the whole network of the social.”

Foucault, 2000 pp.345

One temptation, and risk, with Foucault is to get caught up in an idea that power is a fully installed and instituted force, and one that saturates or permeates all social relations. Confronted with such a force individuals can appear helpless or cast adrift, which isn’t what Foucault meant to do. In our chapter on critical systems librarianship, Simon Barron and I use a Foucauldian approach as a lens to ask questions about power applied to library information systems where one actor, the library, logs data concerning the online activity of another, such as a student or staff member (2018, pp.103-104).

Here I paraphrase from the analysis in this chapter; using Foucault’s method we ask:

- What are the relative positions of power, privilege, and technical knowledge of the actors involved, that permits one to act upon another?

- What are the objectives pursued by the actor in this power relation?

- How is power exercised? For example, surveillance and associated chilling effects, or the implication of disciplinary action based on institutional policies.

- What institutions are at play that determine the site of power? For example, legal structures or accepted institutional practices.

- To what degree are power relations rationalised and elaborated? For example, what technologies or technological refinements are brought to bear in exercising power and are they highly finessed and refined?

Such questions can do a lot of useful work when asked in different contexts about our practice, and to me feel much more approachable when reworked using everyday language and examples.

Ultimately, I feel a critical perspective is something we can all develop and understand by a combination of conversations and listening, experiential knowledge, and also reading texts. Personally I have found critical approaches most helpful when dealing with uncertainty and ambiguity in management and leadership situations, particularly when there is not an obviously correct answer or path. In such situations we rarely have an established playbook to work from, and almost never a handbook to guide us. This is where there is value in taking a critical and reflective approach that combines theoretical and practical knowledge from others’ experience with our own analytical judgement.

“If you are in the game of hegemony you have to be smarter than ‘them’.”

Hall, 1992 p.267

I will finish with a reading recommendation implied by this citation. This is out of context but was too tempting not to cite as my number one recommendation is to read widely within and beyond our discipline, but be smart and selective in how we focus our reading. Stuart Hall here is talking about several competing traditions in intellectual theoretical work in marxism (I will follow Hall’s lowercase usage here), however, I think it works for other spaces where we contest power and confront hegemonic forces.

Acknowledgements

My grateful thanks to the community of #critlib and librarians informed by other critical traditions for ‘the discourse’, and their ongoing helpful suggestions and recommendations.

References

Ahmed, S. (2017) Living a feminist life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Almeida, N. (2018) ‘Interrogating the collective: #critlib and the problem of community’, in Nicholson, K.P. and Seale, M. (eds.) The politics of theory and the practice of critical librarianship. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice, pp. 238-254 [Online]. Available at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/233/

Arendt, H. (1998) The human condition. 2nd edn. London: University of Chicago Press.

Barron, S. and Preater, A. (2018) ‘Critical systems librarianship’, in Nicholson, K.P. and Seale, M. (eds.) The politics of theory and the practice of critical librarianship. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice, pp. 87-113 [Online]. Available at: https://repository.uwl.ac.uk/id/eprint/4512/

Bolton, G. (2014) Reflective practice. 4th edn. London: Sage.

Dhamoon, R.K. (2011) ‘Considerations on mainstreaming intersectionality’, Political Research Quarterly, 64(1), pp. 230-243 [Online]. doi:10.1177/1065912910379227

Dick, A.L. (1995) ‘Library and information science as a social science: neutral and normative conceptions’, The Library Quarterly, 65(2), pp. 216-235 [Online]. doi:10.1086/602777

Foucault, M. (1981) ‘The subject and power’, in Faubion, J.D. (ed.) Power: the essential works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984. New York, NY: New Press, pp.326-348.

Freire, P. (1997) Pedagogy of the heart. London: Bloomsbury.

Hall, S. (1992) ‘Cultural studies and its theoretical legacies’, in Grossberg, L., Nelson, C. and Treichler, P.A. (eds.) Cultural studies. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 277-286.

Hollister, C. (2017) ‘Ten years of expanding the information literacy landscape’, WILU 2017, Edmonton, AB, May 23-25. doi:10.7939/R3X63BJ8M

Horkheimer, M. (1972) Critical theory. New York, NY: Continuum.

hooks, b. (1994) Teaching to transgress. New York, NY: Routledge.

hooks, b. (2003) Teaching community. New York, NY: Routledge.

Nicholson, K.P. and Seale, M. (Eds.) The politics of theory and the practice of critical librarianship. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice

Schopflin, K. (2018) Twitter direct message to Andrew Preater, 18 March.

Smith, E. (2011) ‘Teaching critical reflection’, Teaching in Higher Education, 16(2), pp.211-223 [Online]. doi:10.1080/13562517.2010.515022

Smith, L. (2018) Twitter direct message to Andrew Preater, 3 March.