Why read books, book chapters, journal articles, and other scholarly work as part of your professional development? As a manager, why support and enable colleagues to do so? In this post I discuss some challenges for library managers and leaders in supporting deeper engagement with scholarly work, and some issues in the library profession more broadly with engagement with everything we term “theory”. To be clear, this is a personal reflection on experience not a systematic piece of research; and I am aware I speak from a position of privilege in various ways.

Note on terminology: by ‘scholarly work’ I mean to be inclusive of works of both research and scholarship; if you make no distinction between these terms, no problem. I am using ‘librarianship’ interchangeably with ‘library and information science’ (LIS).

“Pro-intellectualism ftw”

I’ve been thinking about this subject for a while and the vintage 140-character tweets quoted below were fresh libraryland discourse when I started drafting this post. This thread from Chris Bourg about reading and recommending scholarly work in the workplace as an everyday activity, a standard expectation, was the first time I had seen a library director make quite this statement:

Also, not sure why some responses to this train of thought equate "scholarly article" with "theory". Another way to dismiss scholarship?

— Chris Bourg (@mchris4duke) July 17, 2016

wow. The idea that a profession that requires advanced degree is resistant to learning from scholarship is pretty scary

— Chris Bourg (@mchris4duke) July 16, 2016

The whole thread was inspiring and motivational. The discussion in replies made me think about what gives us permission to act in our workplaces beyond the expectations of our roles and job descriptions, and helped me overcome concerns about push-back and reactance that had limited my routinely recommending scholarly work in a work context.

You can put a librarian in a room full of books with access to subject databases but you can't make them read around their field.

— Lauren Smith (@walkyouhome) November 16, 2016

Refusing to engage with professional literature means you're not a professional. GRRRRRRRR. (and also, WEEP) https://t.co/ZVXIzN4K1D

— Emma Coonan (@LibGoddess) February 21, 2017

https://twitter.com/winelibrarian/status/959248381288812551 [deleted tweet]

Spoke to an academic librarian a while ago who laughed in my face for asking if they ever engaged with prof. lit. "NOPE, why would I?" o_0 https://t.co/vrMFbVjHNM

— Lauren Smith (@walkyouhome) February 21, 2017

In these tweets and the exchange between Jessica and Michelle, I recognise both the practitioners’ enthusiasm and frustrations as well as the administrator’s sadness and concern. I am sure many of us can quote analogous examples from experience; I have heard similar thoughts from colleagues.

The reason I identify with these views is that connecting the literature—or theory—within and beyond librarianship to what we do in practice seems such an essential part of practice itself. We can generate knowledge from our practice by reflection and a reflexive stance, but theoretically-informed reflection and application of ideas to practice requires connections outside and beyond practice.

“Thinking is an action. For all aspiring intellectuals, thoughts are the laboratory where ones goes to pose questions and find answers, and the place where visions of theory and praxis come together.” (hooks, 2010 p.7)

bell hooks’s understanding to me shows the integrative relationship of theory and practice, in how reflective thought has a questioning or problem-posing nature. This idea of integrating “theoretical talk”, a term hooks uses to describe writing (1994, p. 70), into practice necessarily implies contextualising others’ knowledge at vital points within our own situation, and using it to improve that situation whether in a personal, interpersonal, or broader social contexts. This view is is rooted in critical theory, which implies a role of theory as liberatory: that is toward constructing an improved social totality (borrowing here Georg Lukács’s term). It necessarily implies reaching beyond our own understandings. On reading, Paulo Freire wrote that:

“Reading is one of the ways I can get the theoretical illumination of practice in a certain moment. […] Information can be got through reading a book, and it can be got through a conversation.” (Freire and Horton 1990, p.98-99)

I feel it is this illumination, a sense of theory shedding light on practice that is the valuable thing we get from directed reading. Despite Freire’s insight about the value of discourse or conversation, reading is a highly practical means of attaining knowledge to inform this illumination. Incidentally, and I digress, We make the road by walking quoted here (dual authorship with Myles Horton, but the quotes are Freire) is a beautiful book and I would recommend it to anyone interested in the purpose of education within a democratic polity.

“Reading, as study, is a difficult, even painful, process at times, but always a pleasant one as well. It implies the reader delve deep into the text, in order to learn its most profound meaning. The more we do this exercise, in a disciplined way, conquering any desire to flee the reading, the more we prepare ourselves for making future reading less difficult.” (Freire 1994, p. 65)

Freire’s position at times can be very uncompromising, with reading a painful but necessary confrontation with new ideas that over time prepared us better for future engagements. The key point I draw from this challenging view is that of learning as an aid to action in practice, that is in ‘actioning’ the theoretical and developing understanding by utilising the theory—or the established scholarly body of knowledge—of our discipline.

In engaging with texts critically we connect with ideas, but the literature also shows what practitioners think possible, shows how we define the limits of practice, and hints toward what is left open to new exploration and discovery. This creative engagement allows us to better think forward to changing circumstances, beyond the basic elements of our technique and immediate cause-and-effect of day-to-day experience. I tend to emphasise multidisciplinary breadth in general reading in comparison to the more focused in-depth research we may undertake for particular projects, however I do think this is a both/and situation. In my experience reading ‘locally’ within librarianship leads toward our local maximum, which may or may not also represent a global maximum. Multidisciplinary approaches help us toward the global maxima, or at least provides points of triangulation outside librarianship that help confirm the coherence of our positions.

For example, in developing understanding of reflective practice I found the literature deepest and most fully-theorised within teaching and health and social care literature. In the social work literature I found a developed concept of critical reflective practice which uses critical theory as a lens for “searching for the assumptions implicit in practice” (Fook and Gardner 2010, p.26) when we iteratively make and remake knowledge in practice. It is impossible for me to say I could have developed the same ideas without this broader exploration.

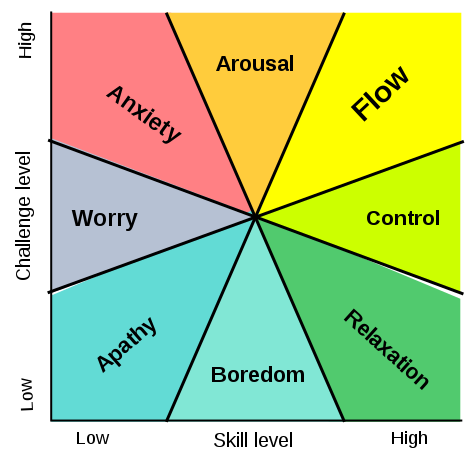

My experience is such learning is a stretch and brings with it discomforting feelings, if not always anxiety or worries. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s (2014, pp.227-238) theory of flow describes how tasks that balance challenge with skill level can achieve a state of optimum performance where our awareness of thoughts, feelings, and action merge.

In encountering and making sense of this theory I initially misunderstood it, as the explanation I heard was based on the idea of optimum performance of everyday workplace tasks. Digging into Csikszentmihalyi’s research and scholarship it became clearer that flow is not necessarily a pleasant experience, which I now recognise in many of my experiences of self-directed learning. The analogy I think best captures my sense of uprootedness or sudden removal from a comfortable place, and the dawning awareness of new knowledge is Sara Ahmed’s explanation of these “ordinary feelings”:

“Every experience I have had of pleasure and excitement about a world opening up has begun with … ordinary feelings of discomfort, of not quite fitting in a chair, of becoming unseated, of being left holding onto the ground.” (Ahmed 2006, p.154)

Time Trades

As well as stretch, I feel focus on areas to develop and improve has to be rooted in self-awareness and self-direction of our practice. I see this type of more directed reading as a purposeful use of our time rather than a chore to be slogged through; and ideally believe self-directed learning can become a habit to work into continual, ongoing practice. I am conscious of and hoping to avoid a sense of investing time for a particular return suggesting the type of neoliberal entrepreneurial approach to education that Sam Popowich (2018) problematises in a recent blog post. Above, a more positive reflection on the value of time is offered in Jeffrey Lewis’s Time Trades.

Practice is in any case more complicated than implied by the idea of theory straightforwardly informing action. In the complex, messy situations of the workplace I rarely perceive a straightforward path where, for example, a colleague has read an article and then implements something based on it. Although I am comfortable quoting from scholarly work to make or emphasise a point in a work context, the notion that we might lay out a 1:1 relationship to colleagues showing how each particular action is rooted in theory belies the mechanics of learning and development and its relationship with practice.

For library work, I perceive the skills needed for this type of focused reading and learning are a key workplace information literacy (IL) skill, understanding that our more academic digital and information literacy skills can be reflexively shaped and developed within libraries-as-workplace. By workplace information literacy, I mean the growing area of research and scholarship that explicitly focuses on IL in workplaces, compared with an academic taught or research study environment where IL is typically learned. A presentation at the 2018 LILAC conference by Marc Forster and Stéphane Goldstein provides an excellent recent summary.

How we can support each other

“Theorizing—even reflection—is seen as a frill in an environment where we are always crunched for time. […] Reading as a means for creating dialogue that develops ideas and affective connections between people does not happen as regularly as it should in neoliberal libraries.” (Coysh, Denton, and Sloniowski 2018, p.130; p.137)

In their book chapter about a reading group set up to read Michel Foucault’s The order of things, Sarah Coysh, William Denton, and Lisa Sloniowski get to the heart of how workplaces often fail to practically support the reflection and dialogue that many of us would agree theoretically is valuable. Being “crunched for time” and lacking a supportive environment are constraints and impediments. Unsurprisingly, the reading group mentioned above took place outside the authors’ workplace in their own time. Likewise, outside work I have always found library workers keen to share reading recommendations and discuss them at conferences and unconferences, in Twitter chats, in conversations one to one. Those situations are those with engaged, self-selected participants who are interested in the subject and want to take part, and as such can be extremely supportive and affirming experiences.

In a recent blog post Carrie Wade discusses the issue of resistance to theory itself:

“The deepest structural issue with library education and publication: theory is treated as something without gravity. Theory is relegated to blog posts by some of our profession’s most brilliant minds—but as a profession we actively denigrate such forms of publication as being of lesser importance.” (Wade, 2018)

I agree with Carrie’s points, and feel this critique should be extended to our ongoing self-directed learning. I believe there is value simply in managers and leadership teams being supportive of, and valuing theoretically-informed reflection and exchange of ideas. In the absence of support, or even hostility to theory, engaging with scholarly work is still highly practical and accessible in many ways: there is no need to ask anyone for permission; no need to wait for training to become available and secure funding to attend it; and is it possible to read widely and in-depth using materials available Open Access or free-to-read, or acquired by other means of legal scholarly sharing.

In senior management roles I have recruited and managed team members in posts that require a postgraduate qualification or equivalent experience. I feel it reasonable to expect these colleagues to be connected with the scholarly literature, keeping up to date, reflecting and relating theory and practice into a coherent praxis of academic librarianship. However, an assumption of needing no support with reading and reflection for professional development can reflect a privileged position. My experience of coming to librarianship via a non-traditional route was that it was a struggle to anticipate and grasp the theoretical approaches and assumptions, and foundational knowledge of the discipline. This wasn’t because the content was intellectually too difficult, but because of the time needed to explore and understand a new area, to learn its language and concepts, and become comfortable enough to engage with established practitioners was substantial alongside working full-time.

Within our professional discourse it is disturbing to see disparaging, if low-level, comments about reading for professional development. This can come across as a lingering wish for gatekeeping and controlling access to knowledge. In opposition to these positions, I ask why can’t all library workers have access to this knowledge—why can’t we support and scaffold each others’ learning? In my experience, sometimes what we need most are supportive environments and inclusive communities as we discover a new “world opening up”.

References

Ahmed, S. (2006) Queer phenomenology. Durham, NC: Duke University.

Coysh, S.J., Denton, W., and Sloniowski, L. ‘Ordering things’, in Nicholson, K.P. and Seale, M. (eds.) The politics of theory and the practice of critical librarianship. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice, pp. 130-144 [Online]. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10315/34415

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014) Flow and the foundations of positive psychology. Reprint, London: Springer, 2014.

Fook, J. and Gardner, F. (2010) Practising critical reflection. Maidenhead: Open University.

Forster, M. and Goldstein, S. (2018) ‘Information literacy in the workplace’, LILAC (Librarians’ Annual Information Literacy Conference), Liverpool 4-6 April. Available at: https://repository.uwl.ac.uk/id/eprint/4801/

Freire, P. (1994) Pedagogy of hope. London: Bloomsbury.

hooks, b. (1994) Teaching to transgress. Abingdon: Routledge.

hooks, b. (2010) Teaching critical thinking. Abingdon: Routledge.

Horton, M. and Freire, P. (1990) We make the road by walking. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University.

Lukács, G. (1971) History and class consciousness. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Popowich, S. (2018) ‘The value of degrees’, Sam Popowich, 4 July. Available at: https://redlibrarian.github.io/article/2018/04/07/the-value-of-degrees.html

Wade, C. (2018) ‘Inquiring the library’, Library Barbarian, 22 March. Available at: http://seadoubleyew.com/inquiring-the-library/

Wikipedia contributors (2018). ‘Flow (psychology)’, Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, [Online]. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Flow_(psychology)&oldid=836178438 (accessed April 13, 2018).