When we launched our new catalogue, Encore from Innovative Interfaces Inc., in June 2011 among the first problems identified by staff and library members was that it did not have a way to request journals from our closed stores (we call this the Stack Service which includes our tower and an offsite store in Egham, Surrey).

This missing functionality between the old and new catalogue was a major barrier to buy-in. Not having it meant staff had to explain three parallel systems for requesting just one type of material from the store. Our readers want to request store material online quickly and efficiently, not have to deal with navigating between two different catalogues.

A new release of the Encore catalogue software has enabled us to rectify this and in this post I’ll explain how. The third request system was paper forms, in case you’re wondering…

Requesting journals

Historical note: Pathfinder Pro used to be part of Innovative’s WebBridge product, which included both an OpenURL link resolver for linking in, and software for presenting context-sensitive links on your record display. Systems librarians at Innovative sites often refer to both products as “WebBridge”.

Requesting journals from a closed store is problematic for an Innovative library if you are cataloguing journals in a normal way – using a holdings or checkin record to detail what you have, rather than itemising each individual journal volume on its own item record.

In our old WebPAC catalogue I had devised a way of using Pathfinder Pro to link out to a Web form that would send some bibliographic data to pre-populate a form. It’s easy to link out to a form from the record (put a link in the MARC 856 for a quick solution) but reusing the record metadata itself helps readers to not introduce errors.

In my opinion Pathfinder Pro is a good product – the tests you can apply are quite powerful including matching parts of your record based on regular expressions and the like.

The basic principle to enable this linking is:

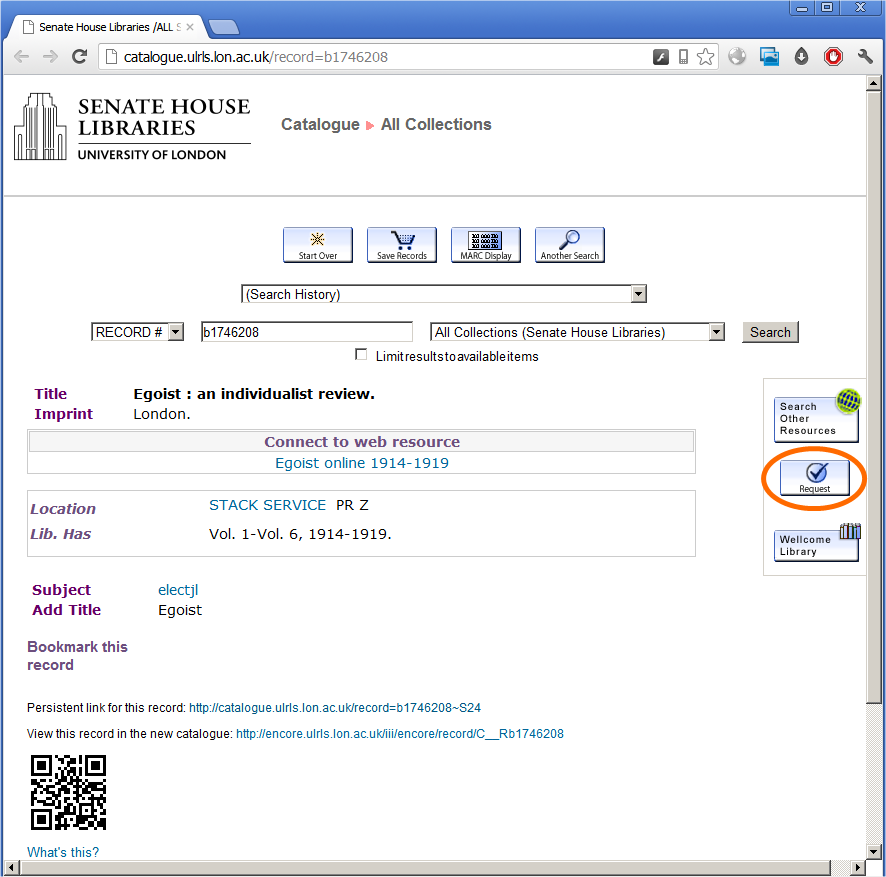

- Check to see if the holdings record is in a store location. Egoist : an individualist review is coded ‘upr’, for example, and a data test in Pathfinder Pro is used see if the holdings record location field equals ‘upr’.

- If the record is a store location, build a link based on selecting the journal title, classmark, and the system record number from the bibliographic record. What is actually rendered on the page is a link using the same icon as we use for other types of online requesting:

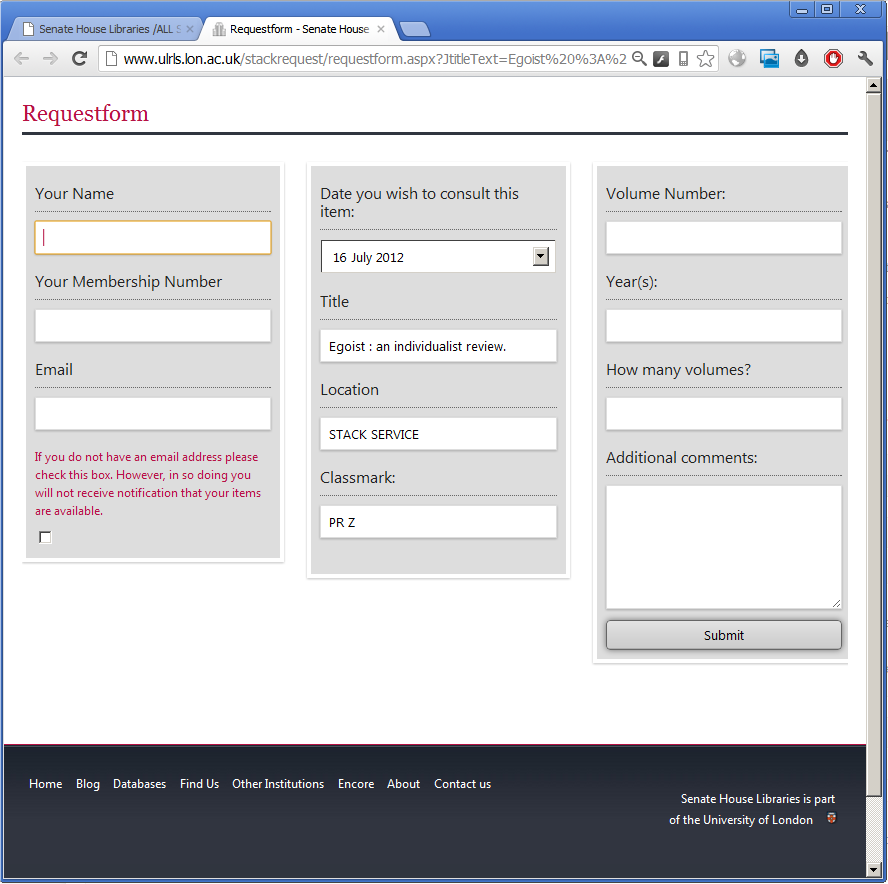

This generates a link to our online request form:

http://www.ulrls.lon.ac.uk/stackrequest/requestform.aspx?JtitleText=Egoist%20%3A%20an%20individualist%20review.&JlocationText=STACK%20SERVICE&JclassmarkText=PR%20Z&JbibText=b1746208a

Which leads to a neatly pre-populated form:

The problem with Encore

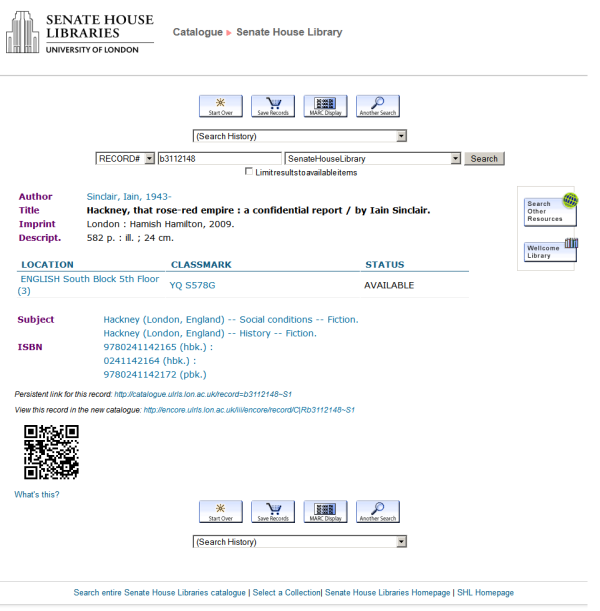

The thing that prevents this working in the new catalogue is Encore lacks the Pathfinder Pro “Bib Table” which allows you to place links on the record display itself. In the screenshot above the Bib Table is the space on the record that contains three buttons, including the store request button circled in orange.

This is a problem as many Innovative sites have built services around this feature of Pathfinder Pro that include placing a link prominently on the bibliographic record.

Towards a solution for Encore

The latest Encore release 4.2 allows you to customise the Encore record display by including your own JavaScript. My presentation on this from the European Innovative Users Group conference 2012 with further examples is available:

I decided there simply had to be a way to insert a link to the store request form into the page using JavaScript…

- Our first thought was using JavaScript to check if the record is in the store, then building a link to the request from by plucking bits of metadata from the page. This was a non-starter as the structure of the rendered Encore page is not semantically sound enough to work with in this way.

- Second thought was to use an Ajax call to scrape the record display of the classic WebPAC which would be easier to work with. This isn’t possible as Encore and the WebPAC run on different Web servers so you run into the same origin policy. And no, you can’t set up a proxy server on your Encore server to work around it.

- Third thought was using a Web application with a dedicated screen-scraping library that that could pull the metadata from the classic WebPAC or Encore. We’d link to this from the Encore record display and allow it to direct the reader’s browser to the populated request form. This is almost what we implemented. Read on…

How to do it

Building a link out from the Encore catalogue is simple. The JavaScript for the Encore record is available as a Pastebin for easier reading.

What this will do:

- Get the system record number. The simplest way I’ve found to do this from the page itself is use the document.URL which contains the record number.

- Check to see if a div exists with ID toggleAnyComponent. Not that you’d know it from the name, but this div is rendered only if there is an attached holdings / checkin record which means we’re dealing with a journal record.

- If if exists, check to see if the div matches a regular expression for the string “STACK SERVICE”.

- If it does match, create a link out to our Web application and append it to the existing customTop div.

This link out appears in this form:

http://www.ulrls.lon.ac.uk/stackrequest/parse.aspx?record=1746208

1746208 is the system record number for Egoist, minus the leading ‘b’ and trailing check digit.

Web application for screen-scraping

The real work is carried out using a Web application written in ASP.NET by my team member Steven Baker. Steve used the Html Agility Pack which is a library for .NET ideal for scraping Web pages. Of course, you can use your favourite language to accomplish the same thing.

Scraping from the Encore or WebPAC record display is a complicated business and how our library has named our various locations and classmarks was not helping.

So instead of scraping the page directly and including lots of different tests to deal with the various oddities found in the markup, it’s much simpler to scrape the WebPAC record display and pick out the div containing the link rendered by Pathfinder Pro.

This link already has the metadata required for the store request form so it’s then just a matter of using this URL to send the Web browser on their way to the request form.

The first step is to load the classic WebPAC page using Html Agility Pack. The link from Encore provides the system record number to generate a link to the WebPAC screen in this form:

http://catalogue.ulrls.lon.ac.uk/record=b1746208

The Pathfinder Pro wblinkdisplay div from the classic WebPAC looks like this for the example of Egoist : an individualist review:

<div class="wblinkdisplay">

<form name="from_stack_service159_form">

<a href="" onClick="javascript:loadInNewWindow('/webbridge~S24*eng/showresource?resurl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.ulrls.lon.ac.uk%2Fstackrequest%2Frequestform.aspx%3FJtitleText%3DEgoist%2B%253A%2Ban%2Bindividualist%2Breview.%26JlocationText%3DSTACK%2520SERVICE%26JclassmarkText%3DPR%2BZ%26JbibText%3Db1746208a&linkid=0&noframe=1');return false;"><img src="/webbridge/image/request.gif" border="0"></img></a>

</form>

</div>

You can see the URL Pathfinder Pro normally redirects the Web brower to. The next steps are:

- Select the div with class wblinkdisplay.

- Cut out the URL based on using “resurl=” and “‘)” at the start and end of the URL to get the indexes needed.

- URL-decode the resulting string.

- Redirect the Web browser to that URL.

In live use, this is so fast that the end user doesn’t realise anything is happening in between clicking the “Request from Store” button in Encore and getting to the request form itself.

Comments on this approach

There are several advantages to handling Pathfinder Pro and Encore integration this way:

- The work to pick out metadata from the record has already been done in Pathfinder Pro and doesn’t need re-implementing.

- This will be easy to extend to other store journals, or if journals move from open access shelves to the store. We only need set up a new location in Pathfinder Pro and it’s reflected in Encore as well. We’d have to do this anyway to enable online requests in the classic WebPAC.

- This approach isn’t specific to journals and could be used to put any links generated by Pathfinder Pro into Encore.

However, this isn’t a complete solution as it doesn’t just give you the Pathfinder Pro Bib Table in Encore. This is what we would really like and what we have asked our software supplier for. That said, if you can pick something unique out of the Encore record to test for then you can link out from Encore in a way that replicates the behaviour of the linking in classic WebPAC with Pathfinder Pro.

Please do contact me with any questions or your thoughts, or leave a comment below.