Last week I attended a round table meeting about bridging gaps between library and information science (LIS), and digital humanities, theory and practice at City, University of London.

The discussion on the day between the group of practitioners and academics and was so rich, interesting, and detailed that there was no way to adequately convey it ‘live’ using social media—though Tweets under the #OATAP hashtag give some flavour of what was discussed. This blog post is therefore a reflective account of the day and an interpretation of what I learned.

Ahead of time we’d been given some framing questions to be addressed on the day, which very much spoke to my interest in the relationship between theory and practice and their potential integration as praxis:

What is the use of theory and how can it be better used to inform practice?

Can researchers and practitioners work together more closely in designing and conducting research, and then interpreting its significance for practice?

What should be the relationship between theory and practice in teaching and learning?

How might LIS schools better serve the needs of employers in developing graduates able to make a significant contribution in the contemporary information professions?

On the day I learned the event was organised under a strand of an AHRC-funded project, Open Access in Theory and Practice (OATAP) which is a joint project between the library schools of City, University of London and University of Sheffield. The project investigates the relationship between theory and practice in the context of open access and the dissemination of research. Despite the title, the questions and small group discussion at the event were not about the theory and practice of open access and scholarly communications, but about the relationship between theory and practice in LIS holistically. I also found out on that day attendees had been invited based on being identified not as theorists or practitioners, but as boundary spanners. This is a term from organizational development theory which means, briefly, a person who can build relationships, create shared meaning, and exchange information across boundaries of various types—in the case of OATAP the focus was theory and practice, rather than for example the departments or networks within and outside our organizations.

In working with academic (faculty) colleagues, one thing I love is getting to see their ability to synthesize information in both breadth and depth in ways that creates new knowledge and insights, and their scaffolding of new understanding in group situations. A point noted, and then deliberately subverted on the day by Professor Stephen Pinfield was that the process of theorizing in research can look like “magic” from the outside. The reality is rather than magic, it is an ongoing and iterative process of creative intellectual work which anyone can engage with; and as bell hooks observes, “one may practice theorizing without ever knowing/possessing the term,” (1994 p.62). As such, everyone can be a theorist and can theorize.

In introducing the day, Pinfield reminded us of a quote attributed to psychologist Kurt Lewin:

There is nothing as practical as a good theory.

Lewin, 1951 p.169

This is a very well-known quote that appears in a variety of slightly different forms in the literature (McCain, 2016). Pinfield quoted the paragraph proceeding this quote, which expands more on the idea of an interrelation between theory and practice:

The greatest handicap of applied psychology has been the fact that, without proper theoretical help, it had to follow the costly, inefficient, and limited method of trial and error. Many psychologists working today in an applied field are keenly aware of the need for close cooperation between theoretical and applied psychology.

Lewin, 1951 p.169

I read an assumption in framings such as Lewin’s of a distinct line between what we think about as ‘theory’ and what we think about as ‘practice’: related, but ultimately separate domains; and the idea of gaps emerging between theory and practice was central to discussion at the event.

One of the general assumptions based on findings of the OATAP research is that we should actually think about theory and practice as more closely related, including ‘cross-fertilization’ between them. I went to the round table day questioning this binary presentation, and despite some limitations of the word ‘praxis’ I wanted to put across an understanding of an integrated ‘theory-practice’ as theoretically and critically-informed reflection and action, drawing on Paulo Freire’s (1997) and Hannah Arendt’s (1998) work.

One of the main things I took from the day was the importance of how the language we use and assumptions about what we mean can shape our collective thinking, or pull us toward particular conclusions. Sharing definitions can be helpful, but in practice doing this is not necessary the best use of limited small group discussion time. I think one of the main benefits of bringing domain experts together in conversation is our ability to rely on our shared body of knowledge and its shorthand, jargon, and slang, in ways that allow us to immediately speak in-depth about the particulars of practice.

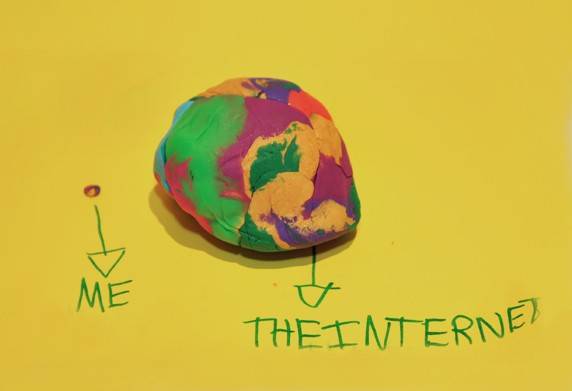

For me, the sum of this body of knowledge within LIS practice is another way of describing what we call ‘theory’. I try not to see theory wholly in terms of abstracted or generalized knowledge, but as knowledge deeply entangled with and expressed within practice. I asked colleagues in small group discussion if we might think about theory-practice as more complicated, more like a ball of plasticine made of a combination of mixed-up colours, rather than neatly-separated domains.

Our experiences of theory and practice

From others at the event I saw a wide range of understandings of theory in work and practice, from the assertion of one researcher that “Theory is my bag!” to one practitioner’s explanation of being highly focused on “Getting on with the day-to-day,” in ways that work against being able to spend time thinking abstractly, to a focus on a facilitation or bridging role between theory and practice described by a practitioner from a sector body. An insightful point made on the day was that researchers and practitioners talk about theory using different terms: practitioners might call something a toolkit or guidelines, whereas a researcher might call something similar a model or a framework. Generally though, no-one is calling these things theory…!

Personally, I feel that centring theory within practice is a key method of developing reflective self-awareness and reflexivity; or in more colloquial terms I ask if we do not seek perspectives and understanding outside ourselves, how do we have confidence we are doing the right things and how do we know what to change? The theme of reflective practice, and in particular being critically-informed as reflective practitioners, was one I found repeated throughout the day. My group discussed an imagined ‘anti-theory’ practitioner, someone who might think of ‘theory’ or the ‘academic’ in a pejorative way. We understood that even those with an anti-theory standpoint will in their practices inevitably use and access abstract and generalized knowledge, because what they have learned about practice themselves and from others will be theoretically-informed. One irony of an “anti-theory” standpoint is that this is itself a theoretical position.

Rhetorically, I asked why wouldn’t you want to start from the most advantageous position as a practitioner—that of understanding many broad, diverse viewpoints from theorists who have already invested time and energy in that creative process? At the event, I noted several theorists and practitioners as influences on my thinking. I’ve written previously about the value of engaging with scholarly work for CPD so won’t retread that ground, but briefly I would be astonished if I could organically come to functionally-equivalent understandings as those I have developed by engaging with colleagues’ scholarship in librarianship and education.

Thinking about constraints, the main issue practitioners explained we face is not having enough time to effectively engage with theory. Secondarily, we felt workplaces in which attention to theory is not valued present a barrier; as do traditional publication formats of journals and expectations of a particular style of academic language.

I had a dissenting viewpoint in this, as I think access to research and scholarship is a more important issue than these points about content and style. Firstly, given the diversity of library and information scholarship published in English globally I suspect that theory-informed research probably is addressing the “right problems”, more likely than work not existing is that I am unaware of it because it is not discoverable. Secondly, in working in libraries as an education worker I have found multidisciplinary breadth in reading and learning from theory necessary, rather than a beneficial but nonessential adjunct—on the day I learned I might expect this from a boundary-spanner. The research we need or can use often being outside our area implies learning from disciplines that are new to us, with a use case very likely unanticipated by scholars in those disciplines. My personal view is in those situations, I find standardized approaches to content and style to be ultimately a help rather than a hindrance, and remain reasonably certain I would not be identified as a relevant practitioner to ‘push’ research toward.

Conversely, the main issue researchers explained that they face is lack of demand from practitioners to be involved with their work and to co-produce research. Libraries as employers do not generally individually commission research from library schools to address the issues facing us, although we do collectively through sector bodies such as SCONUL, so I found this open discussion between researchers and practitioners pointed to a potentially extremely fruitful collaboration. This is an idea I have heard before from Dr Lauren Smith, in her CILIP Conference keynote (2016).

I noticed the small groups had reached very different and varied conclusions about this. One comment I found striking was in reply to the point that we may not have a library school nearby to engage with, it was highlighted that even in situations where a library school and their university library are in close proximity, colleagues may see no more of each other than any other subject liaison roles. Simply having a department close by doesn’t imply deep engagement is easy, any more than being in an academic setting implies engaging with research and scholarship is easy—as ever, the issues are those of building relationships, shared understanding, and trust over time.

Bridging the gap

I found the group discussion on what we can do to bridge gaps, or develop more feedback mechanisms between theory and practice particularly interesting, and it spoke to some challenges relevant to my workplace and our library’s strategic priority for practitioner research and scholarship:

4.5 Enable our staff to engage with and create practitioner research and scholarship, connecting theory and practice in our discipline as well as enhancing our ability to support research and scholarship activities.

Simply put we all broadly agreed that practitioners being involved with theory and theorizing—that is, engaging with and creating research and scholarship—is highly beneficial to individuals and our organizations. The challenge I heard shared by practitioners in senior roles is that writing a strategic priority needs to be followed with material support to enable it, so that it is not treated as an optional extra.

For academic libraries in the UK this might mean introducing a combination of development activities to support enquiry beyond our operational work, as well as a way of tying this development to our appraisal and reward structures. This would in many ways make library workers’ professional development closer in form, level, and function to the type of development expected of academic colleagues for their own pedagogic practice. Within this idea there is potential to link library workers’ professional development to our academic quality standards in a similar way to academics’ own professional development. An insightful observation raised in group discussion is that library workers do engage with pedagogic research and scholarship if they complete a PgCert in academic practice. A final point for critical reflection then, is to ask if equivalent engagement could be possible within librarianship as this qualification is at the same level, with similar expectations of conceptual understanding of research and advanced scholarship?

Bibliography

Arendt, H. (1998) The human condition. 2nd edn. London: University of Chicago Press.

Freire, P. (1997) Pedagogy of the heart. London: Bloomsbury.

hooks, b. (1994) Teaching to transgress. New York, NY: Routledge.

Lewin, K. (1951) Field theory in social science: selected theoretical papers by Kurt Lewin. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

McCain, K.W. (2015) ‘”Nothing as practical as a good theory” does Lewin’s maxim still have salience in the applied social sciences?’, Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 52(1), pp.1-4 [Online]. doi:10.1002/pra2.2015.145052010077

Smith, L. (2016) ‘From the bronze age to big data: why knowledge matters’, CILIP Conference. The Dome, Brighton, 12-13 July [Online]. Available at: http://cilipconference.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Lauren-Smith.pdf

UWL Library Services (2018) Library Services Strategy 2018-23. Available at: https://www.uwl.ac.uk/library/about-library/library-services-strategy

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.