Introduction

This session grew from my thinking about extraversion and introversion in library workers. I was aware of a stereotype of librarians as being introverted, detail-focused, orderly, etc. but in my work I kept meeting extraverted librarians eager to deny that they are anything like that. Indeed, some were surprised that librarianship is thought of as an introverted profession at all.

I thought about a colleague from another academic library who was as extraverted a person as I had ever met. Whereas I was drained and ready for a lie down in a silent, dark room at the end of a day at at a conference, her energy had built steadily throughout the day and she was fizzing with it at the end. I also started noticing where the stereotype did seem to exist, for example a conference I attended where all the libraries seemed to have sent their most introverted staff, and my experience trying to run a focus group discussion with team-members all tending towards introversion.

Having opened with extraversion, you’d be right if you suspected Jung (1971) was my starting point. Following Jung, there are various approaches to classifying personality of which the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is very well-known and widely applied. I personally prefer the Five Factor Model (or “Big Five”), as I’ve found it a better tool for looking at my own personality. The helpful thing about MBTI is that so many people have done an MTBI test, or at least know something about it, and that it has been used as a tool for looking at librarian personalities already.

In that respect we wanted to note we can only discuss what actually exists in the literature – we acknowledge tests used have flaws and limitations.

The landmark paper in this area is by Mary Jane Scherdin (1994). Scherdin surveyed librarians using a version of the MBTI. She found over-representation of introversion in the profession, with the most frequent MBTI types ISTJ (17%), and INTJ (12%). ISTJ is thought of as the classic librarian type: quiet, serious, thorough and dependable, orderly and organized, focused on details, and preferring a logical approach to planning work.

Pitch

Rosie and I therefore pitched this for Library Camp London:

Librarianship is sometimes thought of as the natural domain of a certain personality, in particular the introverted type. We disagree with this, and in this session we will challenge this perception and discuss how a range of personalities are suited to library work. Ahead of Library Camp London on Thursday 21st February uklibchat will be hosting an extra chat on ‘Librarians and personality’ to seed our session with ideas.

uklibchat

Ahead of our session we agreed with the uklibchat team that they would run a one-off special edition of uklibchat on this subject. The agenda is available and there is a very comprehensive and readable summary of the chat from Linsey.. We thought this would be an interesting subject for uklibchat discussion anyway, but wanted to do it for some specific reasons:

- To surface views and opinions from library workers about any underlying truth to librarian personality stereotypes. This would provide starting points or seed discussion at Library Camp London.

- To ask if there were things we could do at Library Camp London to encourage more participation from introverted types. This was in part a response to comments from Library Camp UK 2012 asking for this.

- A major reason was to have the general discussion about this concept ahead of the session itself. In the session we knew we’d have 50 minutes total including about 25 minutes group discussion. This could easily be been eaten up by general discussion. From experience this can be a trap in unconference sessions.

This was a very busy discussion, busy enough for the #uklibchat hashtag to trend on Twitter UK-wide that evening.

We noted people were much more eager than I expected to do a Jungian type test, and discuss the results and what their type meant. There was some buzz about this on Facebook ahead of uklibchat, so we linked to a Jungian test from the agenda. I had been fretting about tests similar to MBTI being viewed as unscientific or worse mumbo jumbo, and I didn’t want to anchor the discussion to MBTI. I relaxed somewhat when people took to it quite easily.

In the chat the most unexpected thing for me was how much talk was about skills rather than personality. I mean by this that skills are something you can acquire, then work on and develop whereas I think of personality trains as a preference we can work with or against in different situations. We realized at Library Camp London we needed to be clear on personality versus skills, and what we were looking for from the group.

An interesting discussion about development opened up on the importance of making yourself do things you would not ordinarily as a way to grow as a person, which would be working against your preferences in personality terms. This was summed up marvellously by Penny as:

@preater RUN TOWARDS THE SPIKES #uklibchat

— Dr Phoenix CS Andrews (@DocPhoenix) February 21, 2013

A darker side emerged when we discussed recruitment or interviewing and the place of psychometric tests like MBTI used to judge suitability for a job. The idea of a person being hired because they will ‘fit in’ to a team based on personality type was seen as especially problematic. My own view is team dynamic is very important, but there are better ways to look at this than a psychometric test. For example, I found an interview where I got to meet the team I’d be working with and be formally questioned by them to be a very good approach.

Library Camp London session

Following suggestions for making our session more inclusive or introvert-friendly, both in the chat and in a very thoughtful and detailed email from Joy, we decided on including a range of activities including a suitably engaging / awful (depending on your view) ice-breaker activity to get people warmed up.

The session was a large one. Obviously we were pleased so many wanted to attend – but I wondered how well the format would work. The ice-breaker was a brief explanation of extraversion and introversion followed by asking everyone to form a rough line based on how extraverted they consider themselves. I was in the middle as an ambivert whereas Rosie took up a position at the extreme extraverted end.

I encouraged the two ends of the line to look at those opposite and think about what they thought of each other in terms of what extraversion and introversion means to them. I think this worked quite well – the extraverted end were keen to start with their discussion points right away, skipping the group work…!

Small group work

We split into four groups, and had two groups each deal with one of these assignments:

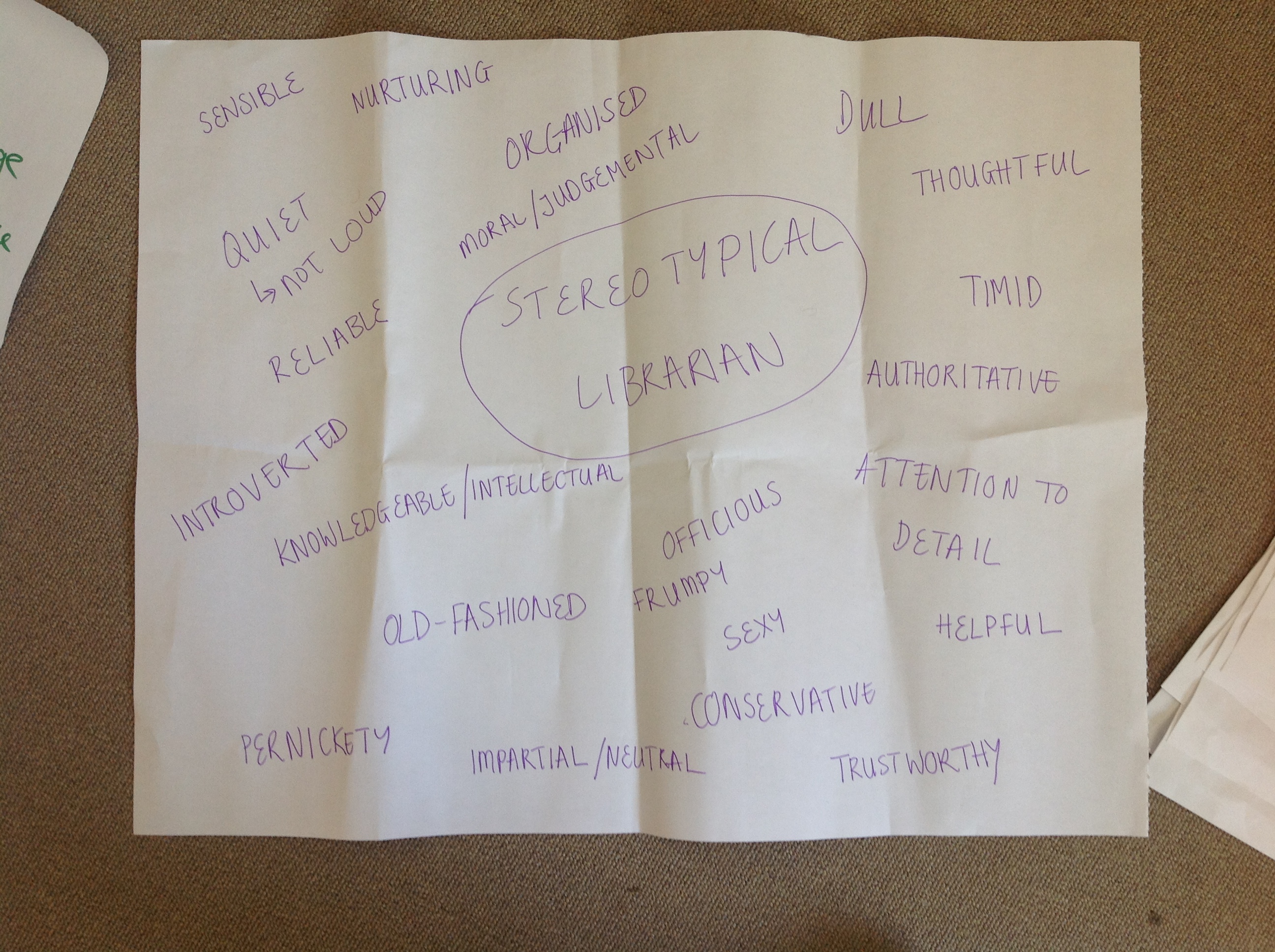

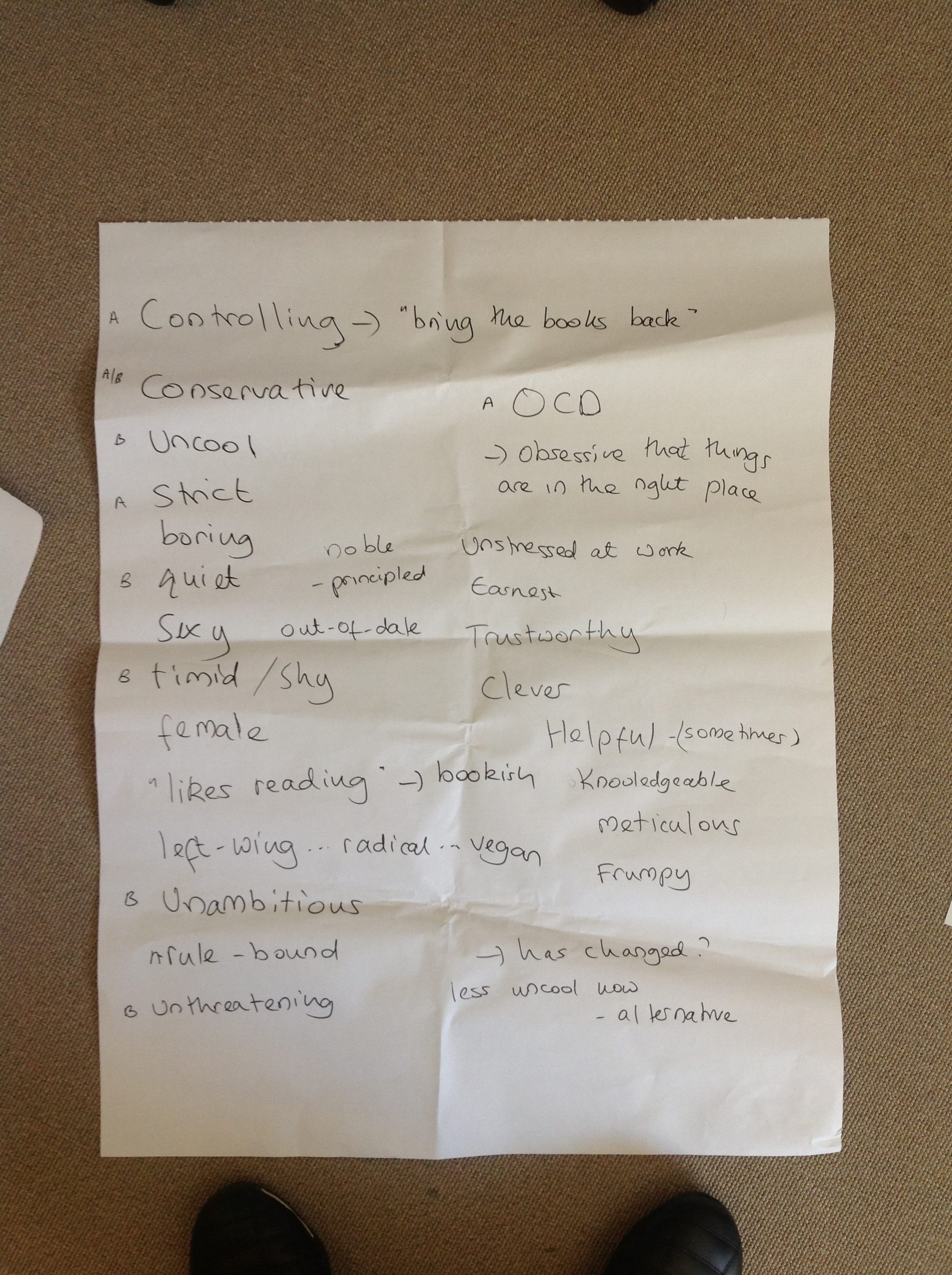

- Write down what you think of as the stereotypical view of a librarian personality seen from outside the profession

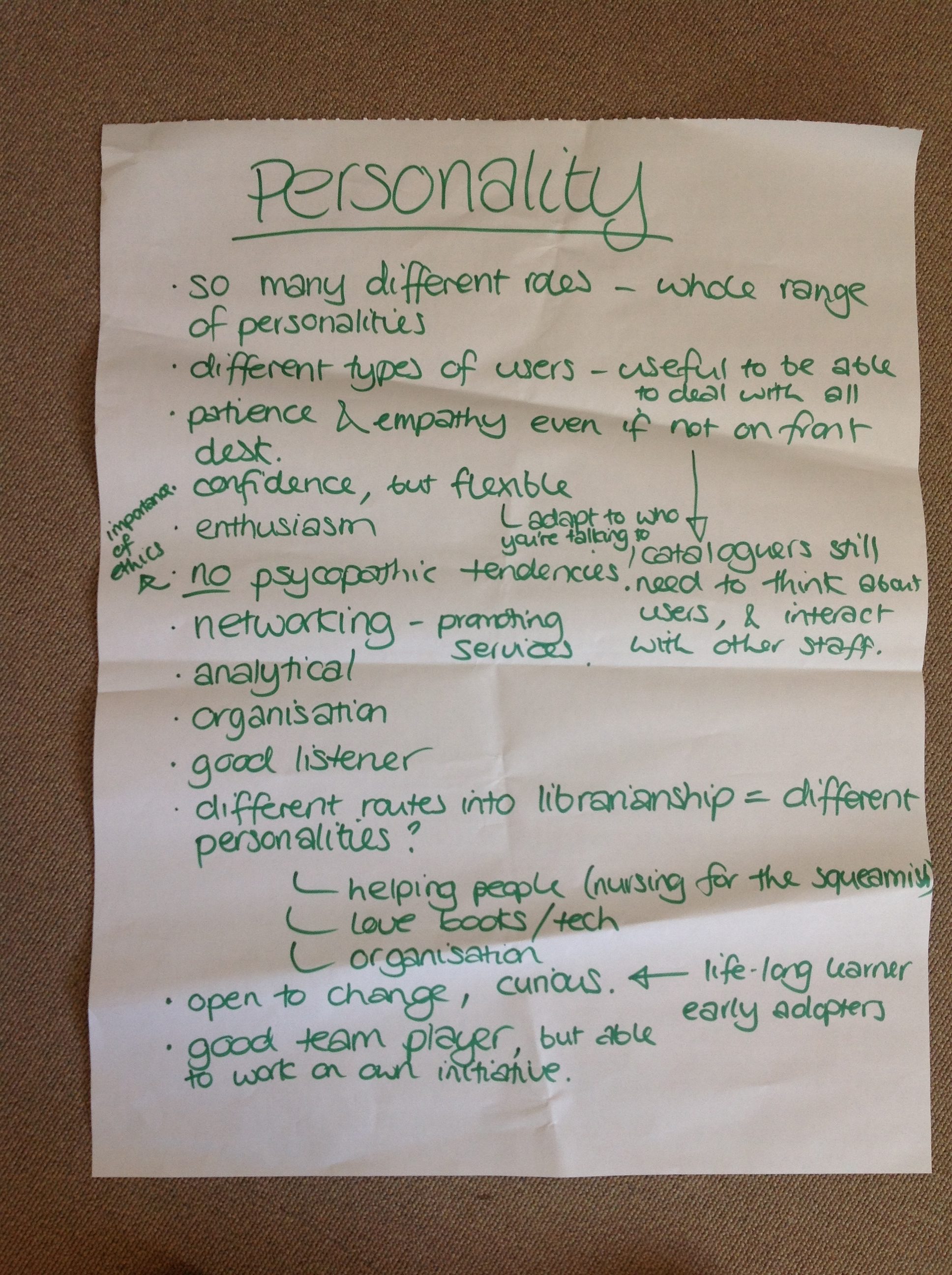

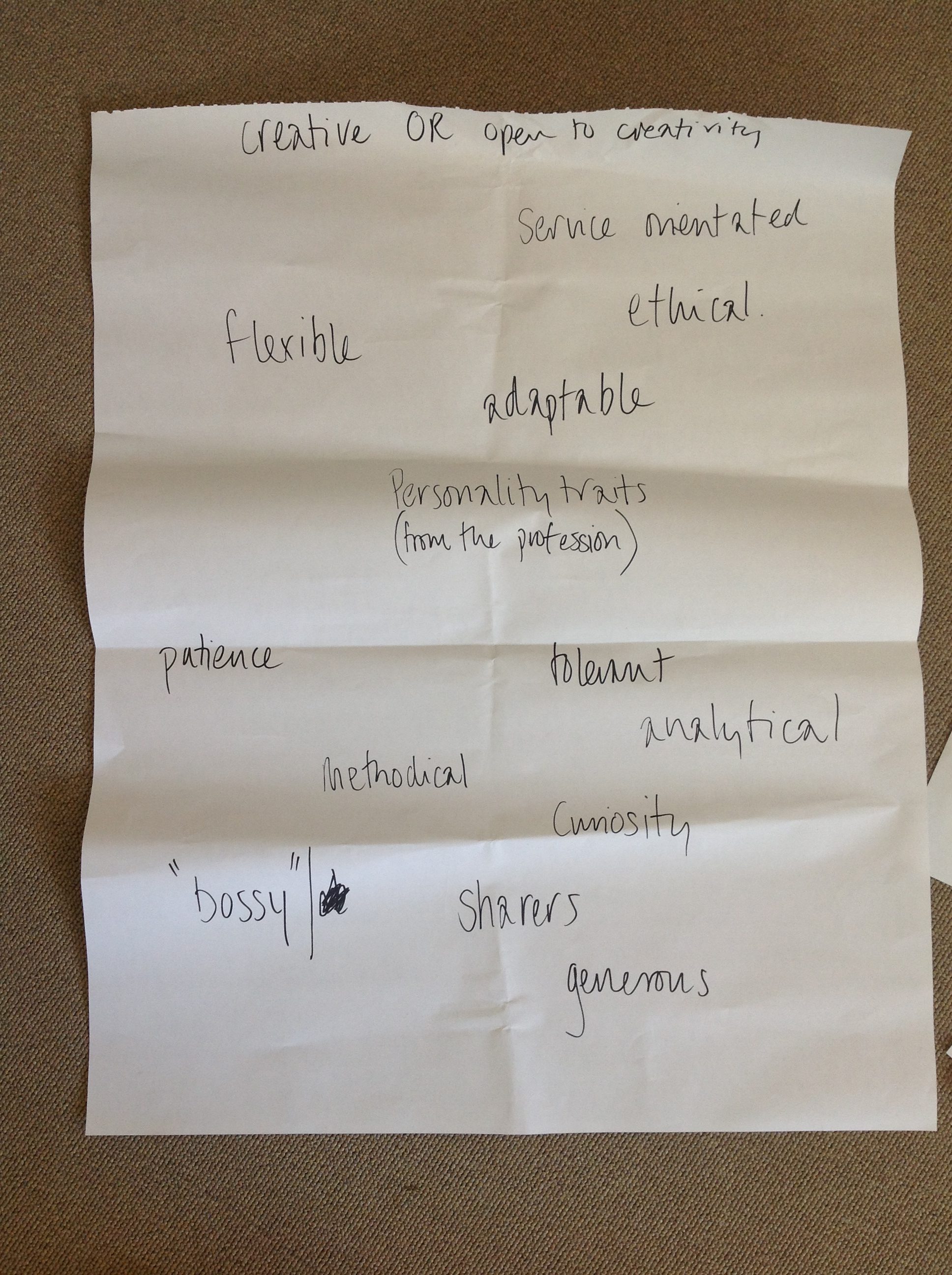

- Write down what you think are the personality traits that are actually needed in modern librarianship

Here are photos of each page:

Group discussion

When we came back together for group discussion, I asking for someone to be brave and contribute thoughts on what they had written. The initial point made was the contradictions from the groups that worked on stereotype, even within the same group, including:

- Sexy and frumpy

- Conservative and left-wing

- Old-fashioned and alternative, cool

Both groups included things that were not personality traits such as being female, but were in keeping with a librarian stereotype. Personal favourites for me were ‘radical… left-wing… vegan’ and ‘helpful (sometimes)’ – I liked how that sometimes brought to my mind a bad library experience right away.

Kathy Baro gave her view that we think about this kind of thing more as its what we do for a living. I wonder if this is librarians being self-obsessed, as discussed at the previous Library Camp Sheffield, or just good at reflecting on what is necessary for our roles and what makes us good at the job? (I err on the side of being positive here.) Looking at the stereotypes, there was a view that we are all quite confident and helpful compared with them – we’re all better than the negative stereotypes we had written down. We were reminded that ours was a self-selected group willing to come to a conference for work in our own time:

Point- how many other professions would give up their Saturday to sit around discussing whether they're introvert or extrovert? #libcampldn

— Helen Rimmer 💙 🔶️ (@melon_h) March 2, 2013

The group talked about the idea that a stereotype can affect the view of people we work with, but also the impression of those interested in joining our profession. We know librarian stereotypes are prevalent within our own organizations – colleagues may be surprised that you are a librarian when introduced. We wondered if the librarian stereotype means people may feel librarianship is a good career based on their introversion or shyness, or think they will get a quiet and bookish environment. This contrasts with how we tend to think of ourselves as outgoing and cool – is there a problem here?

Do attempts to change perceptions of librarians put some ppl off from choosing it as a career choice? #libcampldn

— Victoria Parkinson (@VLParkinson) March 2, 2013

Sam mentioned the usefulness of the enduring library brand being books and knowledge, so there is perhaps value in a library stereotype to identify the core set of skills that sit with these concepts.

I gave an example of personalities in a team context: I worked in a systems team where my manager liked big-picture thinking (intuition versus sensing in Jungian terms), I am very much the same, and my direct report was similar. So if everyone was looking at the big picture, who was going to focus on the details to make things happen? Of course – as Liz pointed out – really these are just preferences and we can work against them. Liz explained her view that a profile like MBTI is helpful as a starting point for self-knowledge. In a team-working situation we might find it effective to mould our approach to our line manager’s preferences, or from a management point of view we could ensure we can work around any missing personality traits.

This flowed into an interesting discussion about power and personality types in our workplaces. The point was raised that unless your organization takes personality on board in some way, hierarchy could just take over and you’re left coping as best you can. Liz’s view was power does come into play to an extent, but a good manager is one that will listen and make adjustments based on preferences.

An example given was a preference for up-front information can come across as confrontational, so it’s important to preface this with what you are going to do about it and why you are asking so many questions. Liz explained personality preference as a way of getting around some of the intrinsic power structures in our organizations – for example it can be a way of depersonalising conflict based on it being an MBTI “thing” or preference when you’re explaining something to a colleague where you know you’ll disagree.

Tying this point back to self-knowledge, Linsey explained that understanding more about how you come across is very useful as a way of getting things done you couldn’t otherwise. I certainly agree with this having worked in flat management structures in education that absolutely require influencing others over whom you have no line management.

Acknowledgements

My grateful thanks to Rosie Hare for her hard work and enthusiasm in developing the ideas behind this session, reading quite a lot of Jung, and co-facilitating the session brilliantly. Thanks also to Liz Jolly for helpful discussion about personality, especially Myers-Briggs types.

Thanks to the uklibchat team – Annie Johnson, Ka-Ming Pang, Sam Wiggins, Sarah Childs, and Linsey Chrisman – for taking on the idea of an additional ‘special edition’ chat, and especially to Linsey for running the chat tightly and efficiently.

References

Briggs Myers, I. (1995) Gifts differing : understanding personality type. Palo Alto, CA: Davies-Black.

Jung, C.G. (1971) Psychological types. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Scherdin, M.J. (1994) ‘Vive la difference: exploring librarian personality types using the MBTI’. In: Discovering Librarians: profiles of a profession (ed. M. Scherdin), pp. 125-156. Chicago: ACRL.